HAVE YOU EVER WONDERED WHAT KIND OF MEMORY SLIPS UNDER YOUR SHOES?

– Carolina Castro Jorquera

My entire childhood was marked by a strong German influence from my father’s family. I studied at the Deutche Shule in San Felipe, a small agricultural town in the Central Valley of Chile. When I entered pre-kindergarten, in 1987, the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet was already coming to an end. I remember it well. During the presidential campaign for the return to democracy in 1990, my parents took me in the van with a flag of the right-wing candidate. I was not aware about all of this until I was much older. When I went to live to Argentina, at the age of 25, I began to understand the political context in which I had grown up. My close circle in Buenos Aires were mostly family members of Chilean exiles.

It was then that Chile’s recent history began to take shape for me. Although still blurry and complex, it became clearer and even some moments of my own family history began to open up. In my house politics were never discussed, or if they were discussed it was always in an evasive way, perhaps because my parents’ position of privilege didn’t allow them to have a critical sense of what had happened during those dark years.

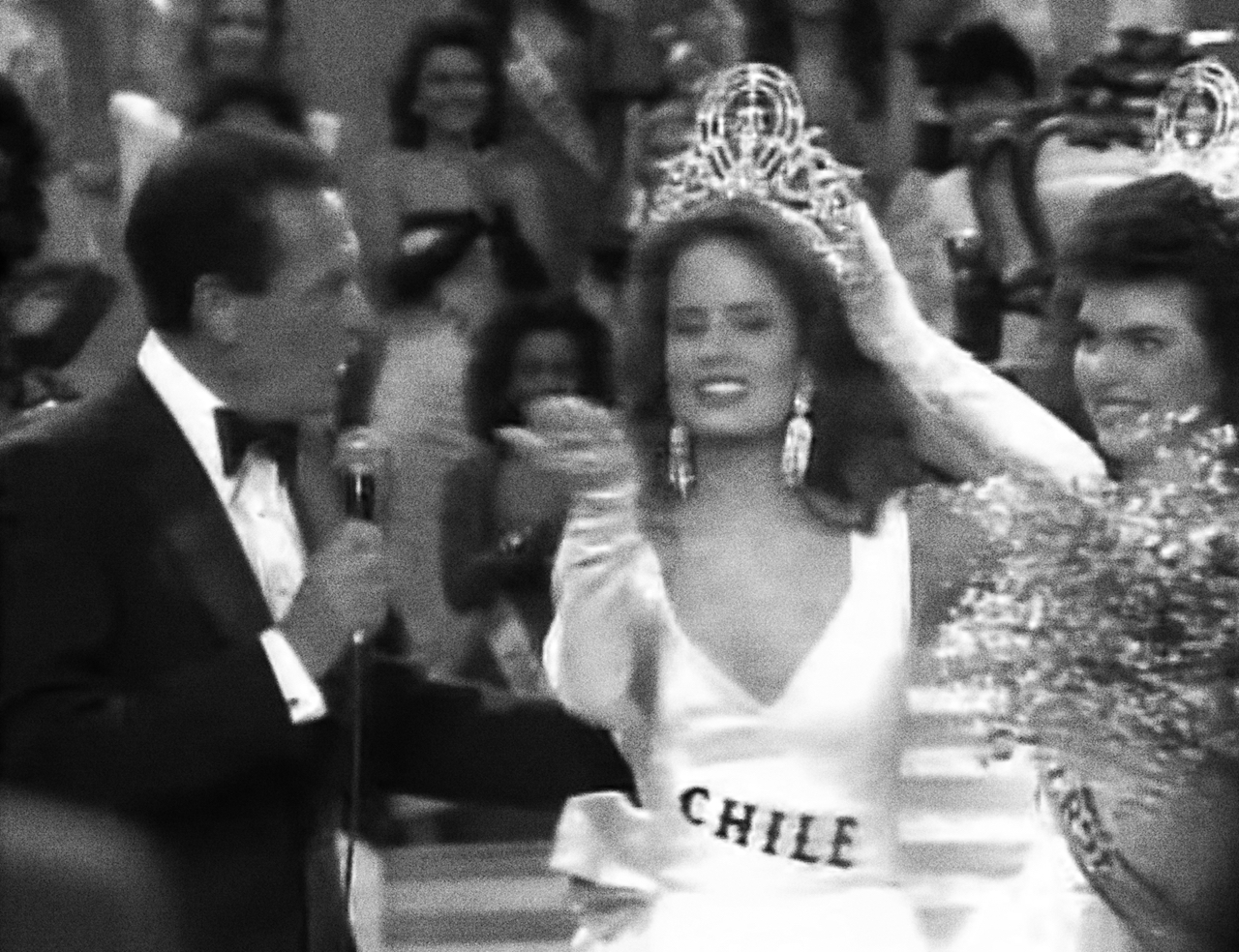

When I first heard Federico Waelder’s words, in the tape that is part of the exhibition “Why aren’t they all like that, as I should be?”, I felt that his critical thinking, camouflaged with irony, was familiar to me. His way of referring to the political moment in Chile was disturbing. I had to listen the tape several times to elucidate whether his position was extremely conservative or extremely radical. The first thing I identified was a surprisingly feminist discourse, if somewhat complacent, around the figure of Cecilia Bolocco, who the day before the recording (May 27, 1987), had been awarded Miss Universe. After giving a series of turns on the subject, he says: “This semi naked eva chilensis has just given us a master class, just as Gabriela Mistral with her pen, Cecilia Bolocco with her plumage.”1 His German accent, wrapped in his radio voice timbre, made me feel that he was giving a serious speech, however, listening carefully I understood that his phrases kept a double meaning.

The news that Cecilia Bolocco was the first Chilean to win the beauty contest gave rise to the national and international press for some months to divert the focus from Pinochet’s policies, enveloping Chile in a superficial aura, with a cheerful news that was far from the country’s reality. However, shortly after the award it became known that Bolocco’s family was close to Augusto Pinochet and a supporter of the fascist regime. This is why Federico’s ironic comparison of Bolocco’s talent with Mistral’s is antagonistic, not only because of the political position of both, but also because Bolocco’s triumph, more than the merit of her beauty, seems to have been a political strategy.

Bolocco’s triumph created a precedent, and with it, a model of beauty that marked my generation. If a Chilean had been Miss Universe, nothing impedes us from being one too. During the nineties, beauty contests, magazines and TV programs abounded in Chile in search of the most beautiful young women in the country. I remember perfectly the applications that my mother would fill out on my behalf so that I could participate. My “European” appearance of white skin and light eyes, were the prototype of beauty that the Chilean middle/upper class was interested in highlighting. As if through our “whiteness,” it was possible to give a modern and advanced image to this “new” country in democracy.

Like Ian’s grandfather, my great-grandmother (Flora Möller) arrived in Chile escaping from Germany, although almost twenty years before Federico, in 1917. The ship in which she was traveling was attacked by bombers, sinking in the middle of the Atlantic. Although her eldest son died, she and her daughter Aide managed to save their lives and reach Chile. Settled in Santiago, a few years later Flora married Carlos Pressler, and my grandmother Edith was born (1933). Their daughters were known as the “most beautiful women in the capital.” Since she was a child, my grandmother showed an ability to play the piano, so she entered the conservatory as a student of the renowned pianist Claudio Arrau. Although she did not finish her studies, being more inclined to athletics, there was always a piano in the house where my uncles and my father grew up; a black Bechstein quarter grand that even I got to “play” when I was just a child.

On the B side of Federico’s tape, there is a piano piece that he recorded as a complement to his presentation. It is curious that, as Ian himself comments, in his speech we perceive this cheerful, easy-going man with a great capacity to express his opinion and feelings, even in a language that is not his own. But in his music, Federico seems to be able to speak on another sensory and sentimental level. The piano sounds sad, even somewhat melancholic. That is perhaps why Ian decides to involve part of himself in the piece and creates this duet in which he superimposes his piece “All My Shoes (Spooky drums no.1)” (2018), a recording of his collection of used shoes falling down a staircase, over his grandfather’s piano, resulting not only in the fusion of a grandfather/grandson piece, but the memory of Ian’s life stamped on his shoes, embracing the only piano piece that holds the memory of his grandfather.

As in previous pieces of Ian’s work, in which the memory of the body is present as a force that transforms matter, in this piece everything refers to corporeality and action, to that close relationship between the palpable and the audible, and how that becomes memory. “Why aren’t they all like that, as I should be?” far from gathering hermetic conceptual forms, is a journey through moments where memory has the possibility of reactivating itself.

1 Translator note:

Federico used a play on words. In Spanish you can use the word “pluma” to refer to a pen. But “pluma” also means feather.