This text is part of the booklet published by Es Baluard Museu d’Art Contemporani, and can be seen in full here.

Conversation between Francesco Giaveri and Ian Waelder

on the occasion of the exhibition “even in a language that is not your own” (2023) by Ian Waelder at Es Baluard Contemporary Art Museum, Palma

Francesco Giaveri:

I was thinking about the stains, and in general of the marks we find in many of your works. Sometimes they call on us to stop and decipher or address something indeterminate, seeking the key to a rebus.

I was thinking of the stains visible on a very latent photograph, almost hidden beneath the shroud of the canvas in your large-format works… Right from the outset we decided that these canvases would not be part of the exhibition at Es Baluard Museu… This was perhaps the only thing we took for granted.

This whole project argues for the possibilities and limits of language, and it does this through a path (indicating the air coming out of the lungs and passing over the larynx and the tongue…) as its central element. However, stains and the unexpected, as in your canvases, are very much present. These are small diversions: footnotes or annotations to the main text that open up ramifications.

The unexpected could be something like suddenly understanding a language we don’t know, that isn’t our own… Recognising meaningful structures and sounds that speak to us at a deeper level than ordinary (even “superficial”) understanding. Like this the stain stops being something nameless and explains itself or simply “explains something”… An indication or a symptom that points outwards, where we look out…

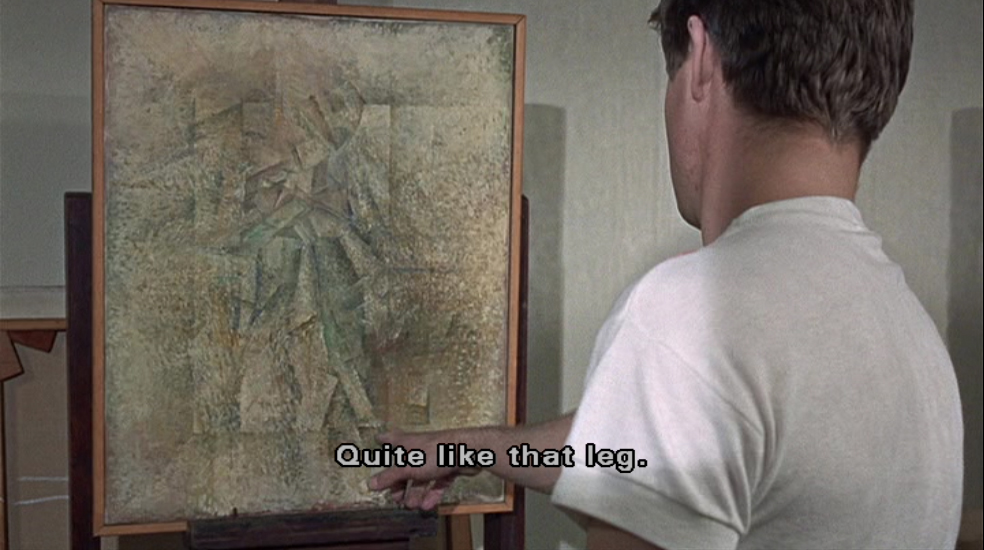

I remember the scene with the painter in Antonioni’s Blow-Up. An abstract painter who confesses to the protagonist that gradually, looking at his work in the studio, he is finding a key to guide him through his own paintings, unlike when he has just painted them, when he “understands nothing”.

Ian Waelder:

The importance to me of the mark, the trace or even the wound has been a constant, going back to my first works in 2012. Since I started working with my collection of analogue cameras, always marvelling at those “scratches” on the negative or the traces of dust that become lines when the copy is enlarged. All this is something that is mirrored in the way I see the city and the objects I come across, obviously inf luenced by over twenty years of skateboarding. Even so, the stain is something that has appeared explicitly in my works only recently, in the last five years.

I see the stain as something invasive, a mark that expands to obscure or simply obstruct the view of what lies behind it. Something that appears when you already knew the previous state of the surface where the stain now is. In a way, this is how I relate to memory, which is the basis of all my work.

With this show we’re putting on, I wanted to take up the challenge of being able to lose myself. To generate a journey that would take in different layers and suggestions in relation to memory. Every corner works as part of this language, this voice we might not know but which sounds familiar. And challenges you to venture down another byway. It is a path full of indications that don’t have to lead anywhere, but that force you to continue and generate different puzzles with the elements which you come across.

FG:

The connection you make between the stain and memory seems relevant. Just as this irregular, shapeless mark covers, wholly or in part, something that was there before, something known that predates the present and which we come across unexpectedly. In my opinion, it is now a matter of interrogating and recognising these signs that persist and have permanently altered the surface on which they have appeared.

I don’t think I can make the stains, but I can receive and suffer them (like the wound you mentioned). So, in your case, do you make the stains? I understand that you don’t deliberately injure

yourself (laughs), though perhaps you expect them when you’re skateboarding?

Here we are going into the concept of accident, of something unforeseen, even if it is deliberately made possible… and above all recognised and isolated in a piece…

I therefore think that we have given great importance to moving through this exhibition, as if it were a track or a setting with a lot of props (maybe a film set?) aiming at or preparing the ideal conditions for the stain or the unexpected to take centre stage, to come to the fore… It is as if in a book, the footnotes took up the centre of the pages in larger type than the main text, tiny and locked away, relegated to the bottom of the page…

IW:

I don’t injure myself deliberately, but I sometimes feel that being an artist is like constantly picking at a wound that doesn’t quite heal.

I’m not a writer, but I tend to understand the exhibition space like a page in a book. For some reason, I always see parallels between writing and sculpture. With regard to balances, rhythm, spaces. How time takes up a space, and how an object can reveal itself very quickly or quite slowly. Like re-reading a story after a while and discovering new connections. It seems to me we have to avoid an overly direct reading, an obvious meaning. Thinking about gestures like writing without accents or punctuation marks, with your eyes closed or while climbing stairs. I see the presence of the journey through this exhibition like a sculpture. It interests me because it seeks to distract and confuse; you have to tie up loose ends between the different sculptures, which are like footnotes about different memories. “Sculptural footnotes”, as I like to call them. Along this route there is time to think and make connections or see oneself reflected. And with this also comes accident, which is in itself already there in the process behind each piece. Using the stain from the cup of coffee spilt on the page.

But it would be very naive of me to claim that everything here is an accident. Of course, there is a lot of scenography, the theatrical or fiction. I’m now thinking a lot about Juan Muñoz or even Andy Kaufman, a master of silence and waiting.

FG:

And also, you don’t drink coffee, right?

Fiction in this project uses the path as a kind of script. This narrative structure is successively “splashed” with little accents or marks that are symptoms or indications that might or might not lead somewhere else.

I think attention and getting lost are very much feelings and actions that this exhibition seeks. Even if they seem contradictory. Attention is necessary, even though it alone does not suffice to understand and establish a dialogue with the other.

Do you think your “sculptural footnotes” are directions on a map or rather little doors to another (more contemplative, dreamlike) dimension? This evocative, rather strange dimension (while reducing gratuitous strangeness to a minimum) somehow seems to lead us elsewhere and I believe the use of audio works emphasises this effect of strangeness, the process of recognising and at the same time losing a clear understanding of what is around us: the sinister. When we stop recognising what was familiar to us.

Then I personally fall back on the Mike Kelley of The Trajectory of Light in Plato’s Cave (from Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile), in which to get into the work and begin the journey you have to crouch down like a worm. The artist forces us to explore the visceral and the first thing necessary is to change posture (physically and mentally, of course), but isn’t this always necessary to establish a dialogue and share a narrative with another?

IW:

Mike Kelley is certainly a very important inf luence. This physical and mental change of posture is always necessary, but faced with a certain passivity or habit you need to take things a little further.

You’re touching on something that is crucial for me, and this consists of the gesture of challenging the viewer one way or another, for the audience not to just be a passive subject. This isn’t something I need in every exhibition or piece I do, but Es Baluard Museu as a venue challenged me to provide an experience that wasn’t necessarily comfortable for anyone visiting the exhibition. Along with Kelley’s irrational side, I admire in paintings the tensions and mazes originating in a rectangle. What I want to avoid and something that really annoys me is how they end up being used as background decoration and reduced to predetermined formats. In this exhibition I want to carry these visual compositions and mazes over to a space to experience that “non-place”, with the option of losing oneself. Keeping an uncanny atmosphere, a certain familiarity, but with a strange aura that tenses the vision and ends up pressing on the whole body.

With regard to memory and my family history, the idea for the title of the exhibition came out of my stay in Germany. Feeling you belong to a language that isn’t your own, and the frustration of observing from afar. The disorientation this causes and the need to reconstruct or expand the gaps of silence.

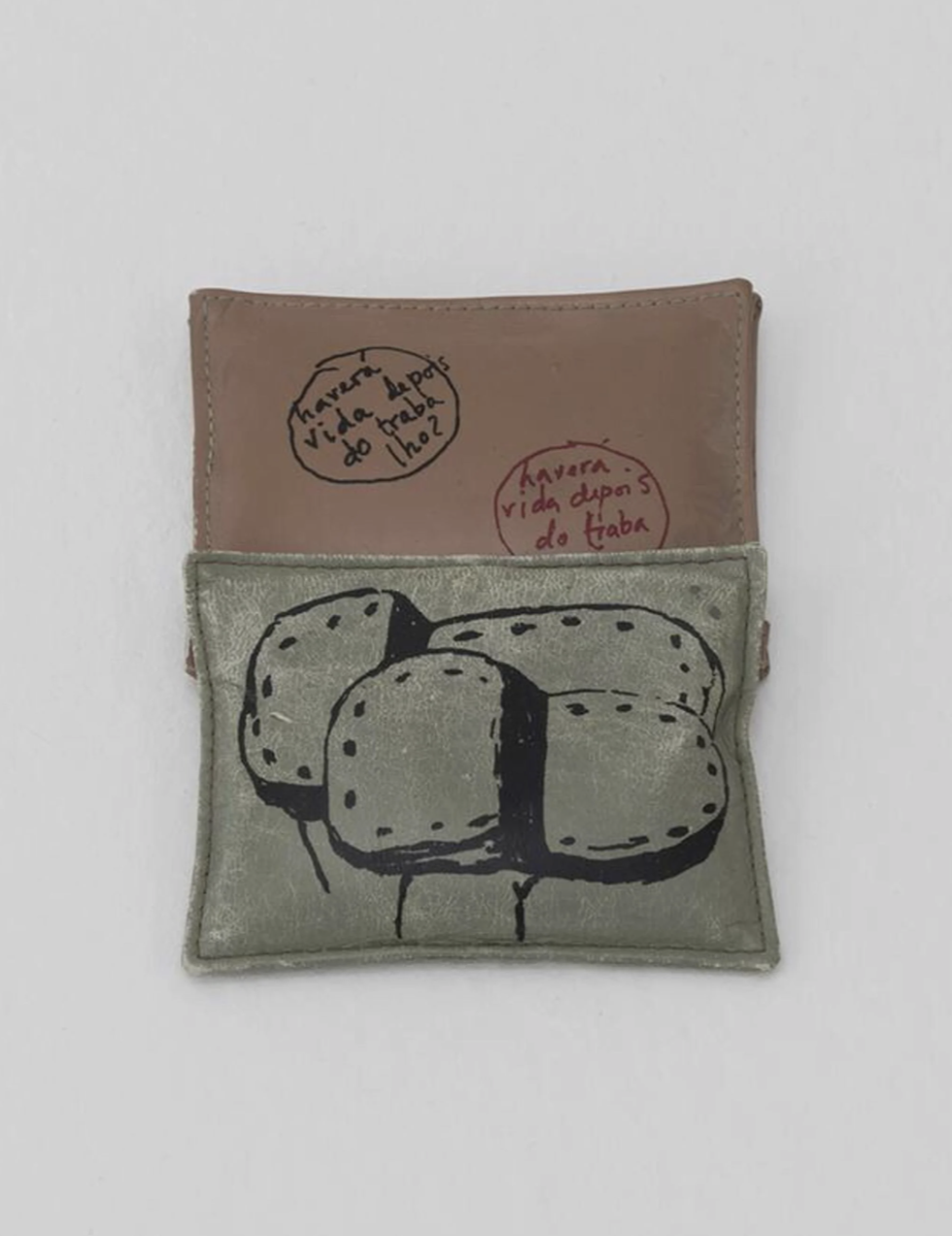

Regarding these “sculptural footnotes”, even though I’d had this term in mind for years, I realised very recently that probably the reference from the “Footnotes” Series by Ana Jotta had slipped in. She’s an artist I admire very much, I even have a piece by her in my own collection. Going back to these sculptures, what they have in common for me is, first of all, that they are not part of a very concrete series, but are simply sculptural annotations like jottings in a notebook. Secondly, they have in common the joining of different small-format objects that have accumulated in my studio or at home for years, waiting for the right time to be used. That’s where they answer me about something, and I intervene like someone doing a drawing around the page. In the case of the show, identity is very much present in the nose, but in a rather ironic way, a reference to a kind of self-portrait. It is a very open-ended element that, while it is deeply rooted in anecdotes about my father, his family and their Jewish past through my grandfather, it can open up different doors for different audiences. This ambiguity does give me a certain margin to move about in more fictional or dreamlike areas, as you say.

FG:

That stands out regarding the “great” Ana Jotta, or could be either the accumulative dynamics of Hanne Darboven in her home-studio, where the objects around you enter into random dialogues and above all you “come across” them unexpectedly, ultimately taking part in a language that is not your own… All this reminds me a little, from the start talking about the route and language, I was thinking about the “zone” in Tarkovsky’s Stalker, full of traps and remains, in a setting that is almost unknown, but also Burroughs’s “interzone” in Naked Lunch… Though maybe to describe this project most effectively we have “Interzone” by Joy Division, on Unknown Pleasures. Rather than a description, this piece of music seems to me almost an invocation… What do you think?

IW:

Absolutely! “Around the corner…”. That gesture of appearance: first maybe the nose, part of a foot, then the eyes. Then the rest of the body. And carrying on round the corner to an unknown place. I think of Venice in winter. Or the Venice of lonely streets in Thomas Mann’s novel. Every step is an echo that fills up a space. As we speak, I still don’t know what form this exhibition will take (let’s be honest with anybody reading this). And I’m really looking forward to getting into the museum rooms and letting myself get carried away by reacting on the spot to whatever I find. Because in spite of my power to control what the space and the works will be, I also find myself in a place of total unknown. And this tension will generate what comes next. In general, we have to abide by certain parameters set by the institution, but this also goes against the nature of many creative processes. And this dialogue or clash is actually a good way of learning.

By pure coincidence, I’ve been reading quite a few texts to do with walking or waiting. I found a passage I liked a lot in Liz Themerson’s introduction to a book by Vila-Matas—Perder teorías [Losing Theories] (2010)—which mentioned the anecdote about Pío Baroja, that on the day the Spanish Civil War broke out he went to the French border, which “was next to his house”. And just like that, like someone going to the bakery, he went into exile in the neighbouring country.